☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼ out of 10☼

Five years after a solid, if nothing-out-of-the-ordinary drama Space Brothers - a prequel to TV series of the same name - Ayumu Watanabe delivers the most ravishing (and daring!) anime feature in recent memory. Right from the get-go, Children of the Sea (originally, Kaijuu no Kodomo) pulls you into the ever-expanding world of its outsider heroine, Ruka (bravura voice performance from 16-yo wunderkind actress Mana Ashida), by simply introducing you to one of her earliest memories - an aquarium brimming with exotic sea life. Drenched in various shades of blue, these initial frames alone hold enough magic to 'spirit you away', yet the immensely talented artists of the acclaimed Studio 4°C don't stop there - oh, no, they persistently cast some pretty strong spells on you all throughout the film.

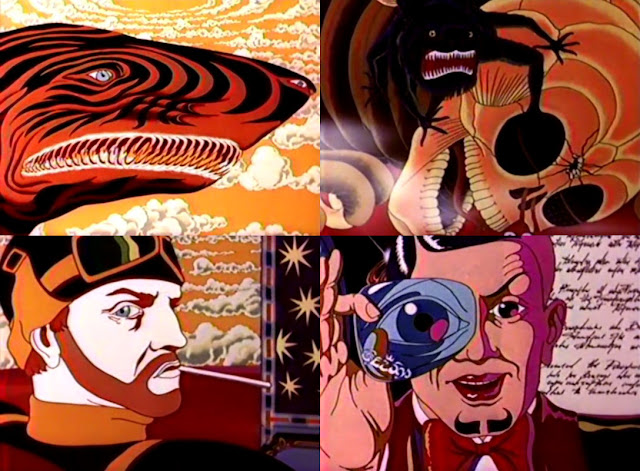

A seamless combination of traditional and computer animation with gouache-like textures makes for the countless picturesque scenes, especially when the 'camera' dives into the water, as well as when the narrative takes a psychedelic turn into the 2001: A Space Odyssey territory. At those moments, the proportions get distorted, the deliberately rough drawing lines break and the colors spill out to generate a dizzying spectacle of abstract patterns and transcendental lights. Equally enchanting are frequent close-ups of the characters' huge, round and lively eyes holding the entire universe(s), and inviting you to look deeper. And what elevates the superb visuals to a whole new level of awe-inspiring is their aural counterpart - the evocative, slightly melancholic score by the veteran Joe Hisaishi who's known for his frequent collaborations with Hayao Miyazaki (hence the reference above). Ranging from minimalist to sweeping, intimate to grandiose, his mellifluous compositions always hit the right chord.

Storywise, Children of the Sea begins as 'a girl meets boy' (actually, two boys) romance / summertime adventure, but gradually evolves into an enigmatic, metaphysical fantasy that links oceans' secrets to cosmic mysteries, and creatures of the Earth to the stars. The transition from the straightforward first half to the increasingly surreal, philosophical second one is effortlessly handled by Watanabe who succeeds in invoking and maintaining the sense of wide-eyed wonder without losing momentum. Allowing the viewers to dream up their own answers, or inspire them to keep searching, he suggests that one's innermost self touched by the purity of nature may pose as the doorway towards the unknown truth(s). In seemingly insignificant aspects of daily life, he finds sublime beauty and reveals its simple wisdom to us, and with great ease, he weaves together many themes, not once letting us be whirled away, let alone crushed by the waves of thoughts provoked by his exploration. Ultimately, in the end of the meditative post-credits sequence, he leaves us with a wonderful line: "The most important promises are not made through words."

A seamless combination of traditional and computer animation with gouache-like textures makes for the countless picturesque scenes, especially when the 'camera' dives into the water, as well as when the narrative takes a psychedelic turn into the 2001: A Space Odyssey territory. At those moments, the proportions get distorted, the deliberately rough drawing lines break and the colors spill out to generate a dizzying spectacle of abstract patterns and transcendental lights. Equally enchanting are frequent close-ups of the characters' huge, round and lively eyes holding the entire universe(s), and inviting you to look deeper. And what elevates the superb visuals to a whole new level of awe-inspiring is their aural counterpart - the evocative, slightly melancholic score by the veteran Joe Hisaishi who's known for his frequent collaborations with Hayao Miyazaki (hence the reference above). Ranging from minimalist to sweeping, intimate to grandiose, his mellifluous compositions always hit the right chord.

Storywise, Children of the Sea begins as 'a girl meets boy' (actually, two boys) romance / summertime adventure, but gradually evolves into an enigmatic, metaphysical fantasy that links oceans' secrets to cosmic mysteries, and creatures of the Earth to the stars. The transition from the straightforward first half to the increasingly surreal, philosophical second one is effortlessly handled by Watanabe who succeeds in invoking and maintaining the sense of wide-eyed wonder without losing momentum. Allowing the viewers to dream up their own answers, or inspire them to keep searching, he suggests that one's innermost self touched by the purity of nature may pose as the doorway towards the unknown truth(s). In seemingly insignificant aspects of daily life, he finds sublime beauty and reveals its simple wisdom to us, and with great ease, he weaves together many themes, not once letting us be whirled away, let alone crushed by the waves of thoughts provoked by his exploration. Ultimately, in the end of the meditative post-credits sequence, he leaves us with a wonderful line: "The most important promises are not made through words."