1. Tár (Todd Field, 2022)

A strong contender for the most razor-sharp performance of the year, Cate Blanchett dominates Todd Field’s impeccably helmed film, as all of its aspects, from Marco Bittner Rosser’s austerely modernist production design to Florian Hoffmeister’s meticulous lensing, seem to be finely tuned to match her nuanced character, maestro and self-proclaimed ‘U-haul lesbian’ Lydia Tár, who – albeit being one of the most unsympathetic big-screen ‘heroines’ – elicits admiration in the (spellbound) writer of these lines.

2. Nattlek / Night Games (Mai Zetterling, 1966)

Freud would’ve had a field day with Mai Zetterling’s sophomore feature – a cinematic provocation that is in equal measures (irreverently) daring and (decadently) beautiful, with Rune Ericson confidently taking the place which Sven Nykvist held in the director’s 1964 debut Loving Couples. Revolving around a man virtually emasculated by ghosts from his past, particularly by a motherly specter, Night Games is a surreal psychosexual drama that erases the boundaries between the protagonist’s childhood and adulthood, as its glum, Bergmanesque tone is successfully dissolved by vigorous eccentricities à la Fellini. Freewheeling and borderline farcical in its approach to the protagonist’s struggle with impotence, both literal and symbolic, it sees captivating Ingrid Tulin having a whale of a time as a narcissistic, gleefully debauched mater familias. Her performance is so charming, that it’s somewhat difficult for a viewer to blame her uninhibited character for the boy’s sexual confusion (and for the man’s incapacity to deal with it), whereas Keve Hjelm’s subtle take on Jan – complemented by Jörgen Lindström’s wide-eyed curiosity – works like a charm in balancing things out.

3. Sevmek Zamani / Time to Love (Metin Erksan, 1966)

‘Male gaze’ gets subverted by a hopelessly romantic twist in Metin Erksan’s quirky, highly poetic, and to a certain degree Antonioni-esque and Czech New Wave-like love story about a poor painter who falls for a portrait of a rich woman. Shot during the late autumn, with frequent downpours, persistent winds and barren trees establishing a thick atmosphere of melancholic longing, Time to Love is gorgeously photographed in high-contrast black and white (Mengü Yegin) which turns virtually every frame into a reason for admiration, complemented by Metin Bükey’s lavishly sentimental score, its roots deep in the Turkish traditional music. Sema Özcan and Müsfik Kenter reach just the right levels of ‘subtle artifice’ in two central roles, making us root for a happy ending, whereby the author often utilizes the strengths of filming locations to externalize inner workings of their characters, directing with a great sense of both pace and style.

4. Freaks Out (Gabriele Mainetti, 2021)

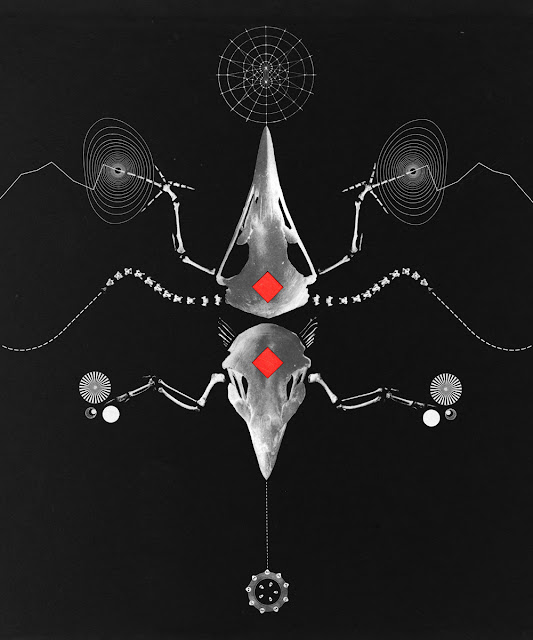

5. Die Verlorenen (Reynold Reynolds, 2015)

Described as ‘a German film from the 1930s that could have been, but never was’, Die Verlorenen (lit. The Lost Ones) marks a fascinating solo feature debut for Alaska-born, Amsterdam-based filmmaker Reynold Reynolds. Both formally and aesthetically challenging, this bold 16mm experiment is a love letter to cinema history, particularly its silent era and early talkies, as well as a delightfully puzzling showcase of its author’s allusive approach to the pictorial language. It follows a young British writer, Christopher, on his stay in an eccentric Berlin cabaret where high art meets burlesque, and science is intertwined with parapsychology, all in a series of dreamlike vignettes that dissolve the Weimar reality. Opening with a ‘God shot’ of a train-set diorama which – if you pay attention – hints at a much faster passage of time, the film fiercely pulls you into a peculiar universe by virtue of its rich texturality and stunning cinematography (Imogen Heath) beautifully complemented by a quaintly avant-garde dialogue between a piano (Gerard Bouwhuis) and a violin (Heleen Hulst). Visually reminiscent of Guy Maddin’s oeuvre, Die Verlorenen also draws comparisons to Werner Schroeter’s work during its operatic bits, one of which is mesmerizingly sung by Croatian mezzo-soprano Tanja Šimić Queiroz.

The film is available on the director’s official Vimeo channel, HERE.

6. The Menu (Mark Mylod, 2022)

Mark Mylod – a chef whose earlier meals I haven’t experienced – serves a spicy anti-capitalist satire, glazed with delicately saucy imagery by veteran DoP (and David Lynch’s frequent collaborator) Peter Deming, and stuffed with slightly honeyed black humor à la Lanthimos and Strickland, as well as with fragrantly meaty performances, particularly from always reliable Anya Taylor-Joy and sardonically dignified Ralph Fiennes. It’s an acquired taste, yet it is as enjoyable as a lovingly prepared cheeseburger and Julienne-cut French fries as a side dish.

7. Anguish (Bigas Luna, 1987)

An off-kilter meta-slasher brimming with unsettling close-ups, and edge-of-the-seat tension, while evoking the memories of some vastly different films, from Un Chien Andalou to Psycho to (Lamberto Bava’s) Demons. And yet, it provides you with a one-of-a-kind viewing experience that makes pigeons and snails appear much weirder than usual...

8. Mona Lisa and the Blood Moon (Ana Lily Amirpour, 2021)

Once again, a girl walks alone at night, but this time her destination is not home – it is unknown. She wears a straight jacket, possesses a mind-control ability, and her true origin is even more mysterious than the smile of Leonardo’s Mona Lisa. Is she an alien? A demon? A result of a secret experiment? Nobody knows. And yet, in a wonderful portrayal by Korean actress Jeon Jong-seo, Mona ‘Lisa’ Lee is a character that you root for right from a get go when you see her bullied by an unethical nurse. She embodies a peculiar combination of childlike innocence, superhero potential and simmering danger, finding a feisty counterpart in a hardened, if opportunistic single mom stripper, Bonnie Belle (an engaging performance by Kate Hudson), and a couple of buddies in frequently high DJ Fuzz (an amusingly eccentric bravura by Ed Skrein in a supporting role) and Bonnie’s 10-yo metalhead son, Charlie (up-and-coming Evan Whitten). Against the bohemian milieu of modern-day New Orleans, these sympathetic outcasts get on with their day-to-day lives the best they can, as Ms. Amirpour washes them in a thick solution of colorful neon light and extremely diversified tunes. There is more style than substance to be found here, but the film’s smooth pacing, actors’ combined energies and easy-going nature somehow keep you invested all the way till the end.

9. Blaze (Del Kathryn Barton, 2022)

In the feature debut from fine artist turned filmmaker Del Kathryn Barton (2015 Crystal Bear Nominee for animated short The Nightingale and the Rose), a twelve-year-old girl, Blaze, struggles to come in terms with a gruesome crime which she accidentally witnessed. Portrayed by Julia Savage whose (micro)acting talent far surpasses her age, the titular heroine escapes into an imaginary world where an army of porcelain figures comes to life at her command, and a sequin-covered dragon embodies her strength, also metaphorizing her transition into womanhood. These phantasmagorical reflections of Blaze’s inner workings is where Barton’s skills as a great visualist really shine, even though they often veer into a music video territory, as she wraps her protagonist’s trauma in glitter without diminishing its indelible impact on the troubled, still-developing psyche. However, it is during the reality bits that her script co-written by Huna Amweero shows the signs of heavy-handedness and on-the-nose-ness, hampering her well-intentioned approach to sensitive topics such as rape, and sexual awakening. Despite its shortcomings, Blaze marks the birth of a unique new voice in modern arthouse cinema, one that is unafraid to speak boldly and angrily, as well as to surprise us with a Wes Craven reference in a film that is much closer to Jim Henson’s and DaveMcKean’s sensibilities.

10. The Lair (Neil Marshall, 2022)

A surprisingly enjoyable, briskly paced and B-movie-esque creature feature that takes a cynical attitude towards both American army & the Soviet past in relation to Afghanistan, demanding to suspend your disbelief about an abandoned, 30-year-old underground facility still being powered by electricity. (Maybe it’s the alien?)