1. Un uomo a metà / Almost a Man (Vittorio de Seta, 1966)

“I do not exist. I feel like I’m dreaming. I look at the other people... Young, happy... How does it feel to be like that? What do they feel? I don’t know. I never felt it. The important thing... is to know.”

Stunningly captured in high-contrast to milky B&W cinematography by Dario Di Palma, and soaked in deep silences and broodingly atmospheric, texturally rich score by maestro Ennio Morricone, Almost a Man is a triumphant psychological drama and an insightful character study that takes the viewer to a dark forest of dreams, memories and fragments from the life of a troubled writer, Michele (the bravura performance by Jacques Perrin). The desperate, disenchanted, sexually repressed and paranoid hero’s slow-burning descent into madness triggered by an existential crisis is directed with a master-level precision and keen sense of cinematic poetry by Vittorio de Seta who creates a hallucinatory atmosphere of oneiric dread, bringing to one’s mind the likes of Bergman, Resnais and Antonioni.

2. Das Totenschiff / Ship of the Dead (Georg Tressler, 1959)

Ship of the Dead is easily one of the most absorbing pieces of (European) classic cinema that I’ve had the honor of seeing. Based on the novel by the mysterious B. Traven best known for The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, it follows an American sailor, Philip ‘Pippip’ Gale, who loses his papers to a prostitute in Antwerp and later finds himself slaving away on Yorikke, a decrepit ship owned by smugglers. As things go from bad yet manageable to virtually inescapable worse for our hero, Tressler demonstrates impressive versatility in helming his vessel across both calm and troubled waters, eliciting a diverse range of moods from the viewer, with little to no effort. Assisted by Heinz Pehlke’s expressive, gritty, noir-like cinematography, and Roland Kovac’s doom-portending score, he creates a number of individual scenes worthy of detailed analysis for their own immense strength, as well as for their irreplaceable value for the film as an engaging whole that is charged with anti-capitalist sentiment. Boosting this adventurous drama’s power is a perfect cast, with Horst Buchholz in a leading role that sees him transforming from a charming, if reckless vagabond into a victim of poor life choices, and Mario Adorf portraying a Stockholm syndrome-suffering seaman, Lawski, whose conflicting friendship with Pippip is the very emotional core of the feature’s darker second half.

3. Popioły / The Ashes (Andrzej Wajda, 1965)

Wow! Epic in scope (the running time is almost 4 hours) and absolutely stunning in its visuals (captured by Jerzy Lipman of Knife in the Water fame), The Ashes is one of the most fascinating pieces of Polish cinema that I’ve seen so far. Andrzej Wajda – assisted by none other than his namesake Żuławski – directs with a painter’s eye, poet’s heart and keen sense of both humor and grandeur, effortlessly transforming into a madman during the scenes of war which dominate the film’s second half. Particularly memorable in its almost surrealist, disquietingly mesmerizing delirium is the chapter Beyond the Mountains which depicts the massacre in the Spanish city of Saragossa. And on its gentler side, The Ashes is no less powerful, grounded in strong performances or rather, sympathetic characters of Rafał Olbromski and Krzysztof Cedro.

4. Girl with Green Eyes (Desmond Davis, 1964)

She is a ‘mixture of innocence and guile’, her favorite novelist is F. Scott Fitzgerald, she puts a sweet smile when someone quotes James Joyce, and lights remind her of ‘all the people in the world waiting for all the other people to come to them’. Contrary to what her bestie Baba (Lynn Redgrave) thinks of her, she does know how to attract men, even though she bites her nails, isn’t very sophisticated and tends to be jealous, possibly because of her green eyes.

Given the film’s (beautiful!) B&W imagery, we can’t see the color, but we can often feel its intensity in the girl’s gazes and glances, or rather, in her youthful vivacity. And Rita Tushingham is extremely charming in the casual portrayal of this lassie, Kate Brady, whose life is Dublin may be a way to escape her Catholic, not to mention sternly patriarchal upbringing in a country. The story of Kate’s falling for a soon-to-be-divorced erudite, Eugene, who’s twice her age (Peter Finch, superb) couldn’t be simpler, yet it works wonders thanks to both Edna O’Brien’s witty, insightful writing and Davis’s refined, inviting and engaging direction marked by great attention to details. Equally praiseworthy are John Addison’s deeply evocative score, and Brian Smedley-Aston’s playful editing, with spatio-temporal ‘jumps’ emphasizing the increasing power of Kate and Eugene’s love.

5. La Prisonnière / Woman in Chains (Henri-Georges Clouzot, 1968)

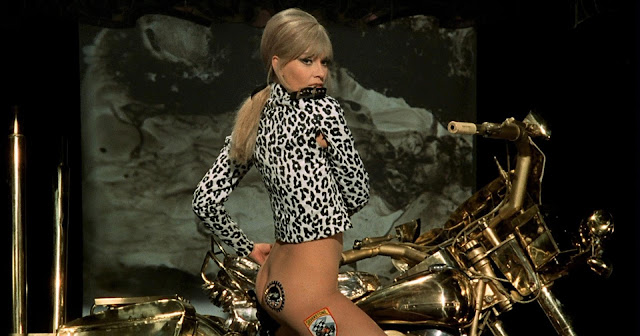

In Henri-Georges Clouzot’s intoxicating swan song whose strange melody brings to mind Peeping Tom, Belle de Jour, and The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, foreshadowing Grillet’s Eden and After, op and pop art intertwine with suppressed passion, as petit bourgeois sensibility clashes with the liberating power of submission. Through the spellbinding use of color, the most mundane of scenes open a door towards über-reality, often signifying (or concealing?) the characters’ mental and emotional states, with the simmering chemistry between Elisabeth Wiener as Josée and Laurent Terzieff as Stanislas creating strong erotic tension. And even when the film appears to have lost some of its steam, the power of visuals alone keep the viewer glued to the screen, preparing you for one of the most psychedelically mind-blowing dream sequences in the history of cinema.

6. Nightmare Alley (Guillermo del Toro, 2022)

Guillermo del Toro’s latest offering - neo-noir Nightmare Alley - made the evening of January 24 for my dear friend Milena and me. Both of us were particularly impressed by the sheer brilliance of the performance from Cate Blanchett who fiercely dominates every scene she is in, as if possessed by the spirits of most if not all of the Golden Age femme fatales. There’s a lot to love about the film, from the great production design to inspired cinematography, but that woman is just out of this world.

7. Black Out p.s. Red Out (Menelaos Karamaghiolis, 1998)

Cinematically opulent, i.e. simmering with wildly varied references overtly woven into an intricate web of sex, lies and audio tapes, Black Out p.s. Red Out begins with a funeral, and ends on the way to a maternity hospital. Imbued with subtle eroticism, it recounts a fragmented, increasingly mystical story centered around an electrified love triangle between a pilot, Hristos, a model, Maria, and a photographer (+ the leader of a secret sect?), Stavros, plunging us into a surreal world that appears as if reflected in a broken mirror. Its main forte lies in hyper-stylized visuals beautifully captured in both color and chiaroscuro B&W by DoP Elias Kostandakopoulos who would collaborate with Antouanetta Angelidi on her 2001 avant-garde fantasy Thief or Reality (also highly recommended). And Fassbinder fans will probably recognize German actress Hanna Schygulla in the role of enigmatic Martha...

8. Szép lányok, ne sírjatok! / Don’t Cry, Pretty Girls! (Márta Mészáros, 1970)

When this film and Valerie and Her Week of Wonders – a seminal work of Czech New Wave – were released, Jaroslava Schallerová was only 14, and yet her confidence and magnetism, even seductiveness in leading roles far surpassed her age. In Márta Mészáros’s rock drama heavy on music and light on dialogue, she portrayed a young woman, Juli, yearning for freedom that had been limited by her brother and fiancé or, generally speaking, traditional values, and what she demonstrated in her performance was nothing short of awe-inspiring. All of those subtle micro-expressions and the way she interacted with both the setting and her partners came across as pure, simultaneously natural and stylized as if she were born in the world of cinema. Simply fascinating! And of course, given that it was Mészáros behind the helm, her face and other faces as well were irresistibly framed in B&W, perpetuated in the most fleeting of moments of love, ennui, delight, melancholy and rumination...

9. Chinesisches Roulette / Chinese Roulette (Rainer Werner Fassbinder, 1976)

Through a glass dirty... Meaningful silences and soul-piercing glances. Contempt and discontent of a dysfunctional bourgeois family, in beautifully shot or rather, ‘choreographed’ frames charged with dramatic tension.

10. Latitude Zero (Ishirō Honda, 1969)

“Politics are only needed by people incapable of running their own lives.”

There’s plenty of extra swinging in this 60’s Japanese-American co-production that out-camps Barbarella with its brilliantly silly B-movie shenanigans obviously inspired by Jules Verne’s writings. Coming across as a live-action prototype of some weird 80’s sci-fi anime, it is deeply rooted in Utopian ideas delivered with a childlike sincerity. Infectiously imaginative, it throws at you everything from a multi-colored smoke of a volcano explosion to scientists in queer outfits to the underwater society that knows no greed and nations, with all-you-can-take diamonds lying around the domed place, and ‘immunity baths’ providing 24-hour invincibility for dangerous missions. Add to that Batman’s mutated cousins, giant rats and a manticore with human brain, and you got yourself an insanely groovy movie which leaves you highly entertained.

11. Жажда страсти (Андрей Харитонов, 1991) / Thirst of Passion (Andrey Kharitonov, 1991)

The sole directorial effort from actor Andrey Kharitonov (1959-2019),

Thirst of Passion is somewhat of an anomaly in Russian cinema. Quite possibly the weirdest film released in what was then still USSR, it stands out as a deeply flawed, yet intriguing multi-genre curiosity which blends everything from gothic horror to giallo to sexploitation to period melodrama to psychological fantasy into a campy piece of cine-madness involving an evil doppelgänger of an unnamed heroine, murderous mirror reflections and mysterious men clad in black one of whom is a ghoulish creature or a vampire. In the leading role credited only as ‘She’, it features Anastasiya Vertinskaya who starred in adaptations of classics such as

Hamlet,

War and Peace and

Anna Karenina during the 60’s, and portrayed the love interest of

Amphibian Man (1962) – a lovely sci-fi romance I ‘discovered’ in 2021. A bold and beautiful nonsense marked by ‘glowing’ cinematography.

12. L'éveillé du pont de l'Alma / The Insomniac on the Bridge (Raúl Ruiz, 1985)

“Seeing a chimera is not impossible, the chimera itrself, that's another thing.”

The strangeness of this film should be measured in indivisible dream units... or in the words uttered by shadows, perhaps?

13. Eyes of Laura Mars (Irvin Kershner, 1978)

Hollywood goes giallo, with exquisite performances from Faye Dunaway and Tommy Lee Jones in leading roles.

14. Una sull'altra / One on Top of the Other (Lucio Fulci, 1969)

At his most Hitchcockian, Fulci delivers a delightfully sleazy and visually pleasing thriller that feels like a precursor to some 80’s and 90’s additions to the genre, with Riz Ortolani’s godlike jazz score pulling you deep into the world of deceits, sexy doppelgängers and murderous jealousy.

15. Sanctorum (Joshua Gil, 2019)

“Humankind sees the world through suffering. They walk like a lost child. Not knowing what they are looking for. Not knowing what they have. Only love can save them.”

16. Meng jing ren sheng / I Dreamed a Dream (Qihua Duan, 2021)

Shihao Li: “30 seconds in reality is an hour in dream time.”

Liying Zhu: “But, we’re not dreaming!”

Shihao Li: “Movie is a dream.”

Dreams, memories and reality are densely interweaved in the ambitious if flawed directorial debut from Qihua Duan, as a protagonist, Crystal, tries to uncover the secrets from her comatose father’s past through the technique of ‘dream yoga’ which allows lucid dreaming. An exploration of sub- and unconscious mind, her meandering journey takes the viewer through the labyrinth of Rashomon-esque structure, thematizing young love, rivalry, betrayal, and traumas turned into healing fantasies. Amongst numerous characters who – as both their younger and older selves – slip in and out of each other’s oft-fabricated stories, one can easily get lost, yet by the end Duan manages to tie all the narrative threads together, for better or worse. Where his film excels is the stylish cinematography coupled with great, occasionally baroque production design, and complemented by gentle, romantic score.

17. The Flower Thief (Ron Rice, 1960)

In what appears like a neo-Dadaist experiment conducted in a freewheeling way, Warholite Taylor Mead embarks on a San Francisco adventure of pure randomness and oft-childlike lollygagging captured in grainy 16mm imagery and accompanied by wildly eclectic score, with Rice’s playful editing adding to the film’s loony sincerity.

18. Hayop ka! / You Animal! (Avid Liongoren, 2020)

Ralph Bakshi’s cult feature debut Fritz the Cat gets a sort of a spiritual successor in romantic satire You Animal! – a tongue-in-cheek parody of Pinoy telenovelas in which characters reportedly scream the titular phrase at each other in the heat of an argument. Deliciously saucy and irreverently melodramatic, it revolves around a love triangle between a saleslady or rather, salescat, Nimfa, her macho mongrel boyfriend, Roger, who works as a janitor, and a purebred (husky?) playboy industrialist, Iñigo Villanueva, with whom she fulfills her fantasy of climbing up the social ladder. (Did I mention that the story is actually prophesized by an octopus fortune teller?)

The colorfully mesmerizing artwork may look cute, with all protagonists being talking animals, but this is by no means a kids cartoon, given its rampant sex jokes and lines such as ‘my bun is quite content with your hot dog’, not to mention a highly stylized (read: deliberately kitschy) intercourse scene. However, it is not to be taken too seriously either, which Liongoren and his team of artists constantly emphasize through visual gags such as witty inscriptions hanging all around ‘Zootopia-fied’ Manila, some literal catfight or a rage-fueled scene inspired by the Street Fighter car-crashing bonus game. The social commentary is there, but it is the animators’ wild and free imagination that comes first, reflected in a wonderful world building, and full control of the medium.

19. The King’s Daughter (Sean McNamara, 2022)

After facing zombies, infected dobermanns and other mutant creatures as Claire Redfield in lovingly trashy true-to-game adaptation Resident Evil: Welcome to Raccoon City, Kaya Scodelario jumps with great gusto into elegant dresses as the titular princess, and makes a contact of the mermaid kind (so, there’s also a lot of jumping into the water). Her father is a historical figure known as le Roi Soleil, but it’s best you forget about the facts, because what we get here is a work of pure, decontextualized fiction (well, I already mentioned the mythological maid of the sea, didn’t I?).

Being a big sucker for fairy tales, I found The King’s Daughter to be quite an enjoyable, throwback-to-the-childhood experience, in spite of all the (compulsory?) clichés and predictable outcome of the story which is loosely based on Vonda N. McIntyre’s novel The Moon and the Sun. Innocently romantic, baroquely flamboyant and playfully anachronistic (I couldn’t be gladder they decided not to include those terrible wigs of the period), this high fantasy boasts dazzlingly colorful visuals assisted by slightly outdated, yet beautiful CGI reminiscent of Chinese cinema, which should come as no surprise given that half of the budget was reportedly provided by China’s Kylin Films. (Not to mention that the mermaid is modeled after Bingbing Fan.) Lending it some serious gravitas is the trio of veterans, Julie Andrews as the Narrator, Pierce Brosnan as King Louis XIV, and William Hurt as his spiritual guide, Pere La Chaise, all of who seem to enjoy their roles. Scodelario proves to be an interesting choice for convent-raised, but rebellious, musically talented and of course righteous Marie-Josephe D'Alembert whose heart gets stolen by a ‘commoner’ that is adventure-seeking fishermen captain, Yves De La Croix, portrayed by Benjamin Walker.

20. Iris Warriors (Roydon Turner, 2022)

Awww... this was sweet!

Somewhere in England, during the WWII bombings, a group of children and their teacher, Miss Shaw, get trapped in a cellar. To strip away the young ones’ fears, she reads them a story of Darkness and Light, and of their offspring – seven colors known as Iris Warriors. The book seems to have magical powers, so the brick wall in the candlelit shelter turns into a portal towards the mythical world whose inhabitants – adorned in ‘spiky’ costumes – dance the lovely fairy tale on a diamond-shaped entity floating in space. Paired with on-a-budget, yet attractive visuals, the simple narrative works well in stimulating imagination, even though the viewer can predict the happy ending coming its way. Transcending the tale’s familiarity are the soothing voice of Jessica Brown Findlay perfectly cast as Miss Shaw, and striking combination of angular (some may even say obsolete) CGI with stagey mise-en-scène. Iris Warriors is not a masterpiece, but it’s unorthodox style is what makes it worth a watch.

“You can dance anywhere, even if only in your heart.”

Honorable mention:

Post Mortem (Péter Bergendy, 2020)

In Péter Bergendy’s horror debut set in a Hungarian village after the WWI, ghosts manifest as shadows who whisper, moan and sigh creepily, lifting the living up in the air when not moving and throwing various objects around. A young post mortem photographer, Tomás (Viktor Klem), joins a 10-yo girl, Anna, whose face appeared to him during his near-death experience, to discover the reason(s) of haunting. Not trying to reinvent the wheel as many of his contemporaries do (only to fail miserably), Bergendy employs some good ol’ scare tactics and they work like a charm that makes all of your bodily hair raise. Assisted by the bleakly picturesque cinematography of withered colors, befittingly chilling score, and skin-crawling sound effects, he establishes a dense, immersive atmosphere which, to a certain point, dissolves in the final chapter of a Hollywood-like VFX trickery threatening to turn the film into a parody of the genre. However, even its most problematic section provides some beautifully poetic moments that manage to anchor over-the-top goings-on to a solid ground.

No comments:

Post a Comment